There are many things to consider when creating a knife. In this page I am going to go through various construction types, the different steels I use for the blades and terms that I may use when talking you through a knife that you might want to commission from me.

Construction

There are three basic types of construction that I use for my knives (with variations among these three), each has its own advantages and disadvantages, many of which will be down to an individuals preferences

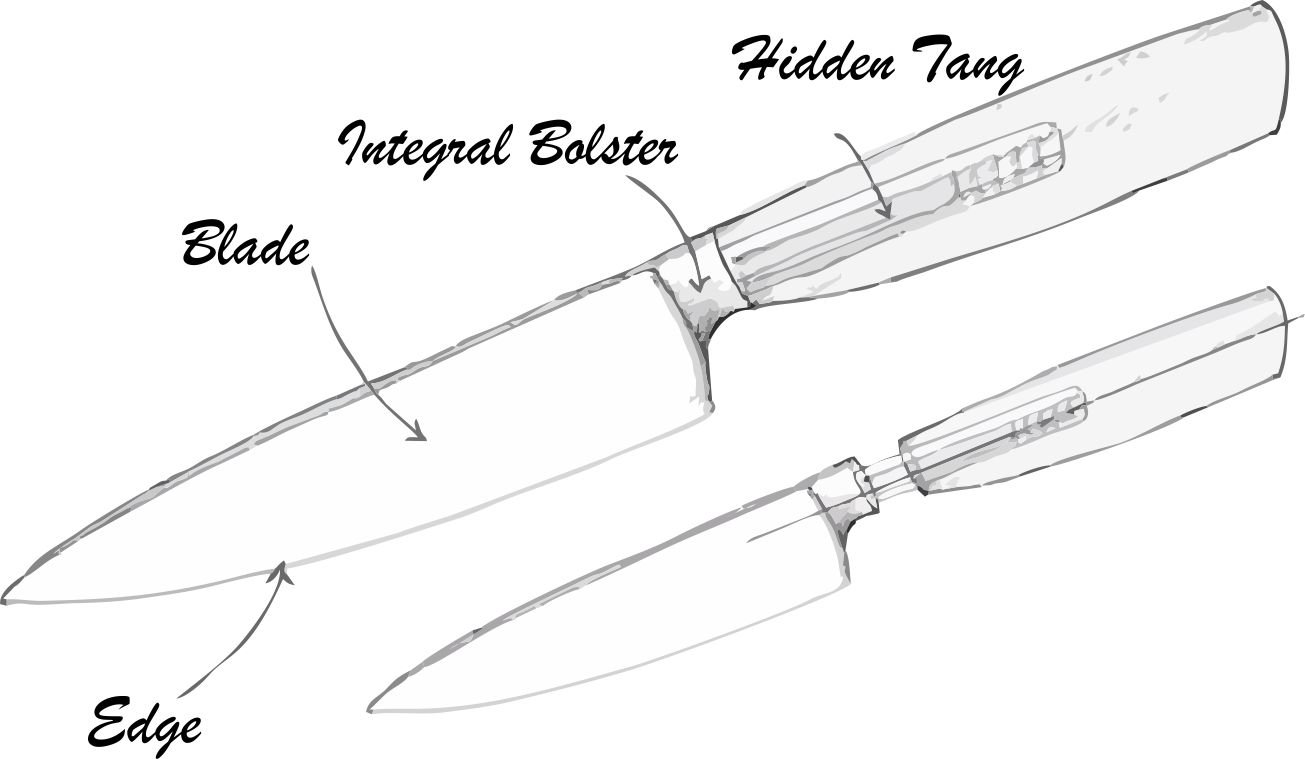

Hidden Tang

Often used on Japanese knives, this construction style is favoured for the lightness it offers, leading to a well balance knife that feels nimble and quick in the hand. I use this construction style often as well as it can really show off a nice piece of wood for the handle. On my knives I usually run the tang all the way through the handle where I thread the end and secure from the back with a ‘Corby bolt’, thus giving the handle a mechanical connection to the blade. I tend to use this construction style on blades such as; Gyuto’s, Santoku’s, Nakiri’s and Petty’s.

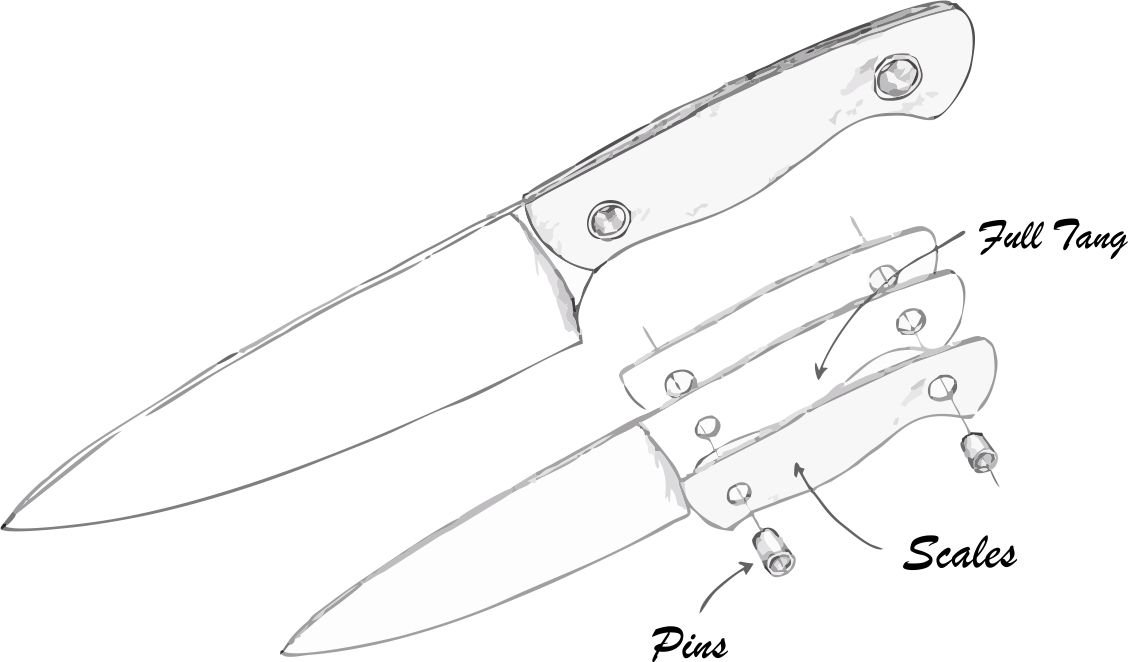

Full Tang

The most common construction style in the western canon, the full tang offers durability, suitable heft and simplicity of construction. I favour this construction style for most of my mono stainless steel knives as it offers the most cost effective way to build a knife that will last a lifetime, while still giving you the performance of a more expensive blade. A construction style that lends itself very well to most blade designs, there is a reason why this is one of the most popular ways to build a knife.

Integral Bolster

My personal favourite construction style is the Integral Bolster. With the blade material flowing seamlessly into and forming part of the handle, this construction offers comfort in the hand, a lovely balance due to the weight being centred and a nice heft. It also in my opinion showcases the greatest level of skill and offers a uniqueness and elegance of craft. Most especially when using Damascus steel, where the pattern will flow up into the handle transition. These are among the most expensive knives I make due to the extra material that needs to be used in the forging when isolating the bolster as well as the extra time it takes to grind and polish the contour of the bolster transitions. This construction style suits perfectly a classic Chefs knife, a big Gyuto and Hunting knives.

Steel

There are many choices to make these days in regards to excellent knife steels, here I will take you through my favourites.

Stainless Or High Carbon?

Carbon steel and stainless steel have the same basic ingredients of iron and carbon. Their main difference is alloy content—carbon steel has under 10.5 percent alloy content, while stainless steel must contain 10.5 percent chromium or more.

This isn’t really the place to get into all the vagaries of Metallurgy; a huge field in its own right and one that our industrialised civilisation is built upon. Here i’m just trying to outline the very basics for you, if you prefer a deeper dive I would suggest Dr. Larrin Thomas’s book - Knife Engineering: Steel, Heat Treating, and Geometry.

That being said, here are few differences you should know (not all these points hold true for all the various different alloys out there, and there are plenty of exceptions so please treat this as it is intended; an overview).

One of the main and most obvious distinctions between high carbon and stainless steels is the fact that due to their Chromium content, stainless steels benefit from increased corrosion resistance that means that they are far less prone to rusting and staining when coming into contact with acids. A carbon steel knife on the other hand will rust if left wet. If properly cared for this can be avoided and over time your knife will form a protective patina which will add to its unique character.

Another thing to consider is edge retention. Generally speaking, a stainless steel knife will be better at keeping an edge for longer than a carbon steel knife, however the stainless steel knife will be harder to sharpen. This is due to the fact that Chromium Carbides are harder than Iron Carbides. There are other metals that can be alloyed into steel to increase hardness, for example Vanadium or Tungsten and you can find carbon steel with these in, for example 52100 or Wolfram.

Damascus Steel

The two steels that I, and most people, use for making Damascus steel (or pattern welded steel if one is being pedantic) are 1095 and 15N20. 1095 is a plain carbon steel with 0.95% Carbon, and 15N20 has some Nickel in it. When these two are stacked, forge-welded together and then contorted and layered in different ways, you can achieve a pattern in the blade itself. Once the blade is ground and polished, it is submerged in acid and the different layers are revealed as the Nickel in the 15N20 causes the steel to resist the acid more than the plain 1095.

Is Damascus steel better than the sum of its parts? In short no. It is purely done for aesthetic purposes and to showcase skill and craftsmanship. You may have notice that my favourite pattern is Feather. Its not something that a lot of people do and really makes for a unique, beautiful blade.

Hot splitting steel to create a feather pattern

Stainless Damascus

Stainless Damascus steel is a very specialist material. There are only a few companies that produce it. I use two of these, Damasteel made in Sweden and Takefu Coreless made in Japan. Both use extremely good steels in their Mix and are the best performing I have come across. The option is from Takefu is limited to a bar of layered but unpattern steel that I pattern from bar stock. Damasteel comes in a whole range of different patterns and is widely considered to be the best knifemaking steel out there (it comes down to preference at the end of the day). These steel aren’t cheap but they are my new favourites for the way they perform. They are harder to work with than carbon steel, the forging is a lot harder as is the finishing which means that I charge a premium for blades in these steels.

Mono-Stainless Steels

For practical, utilitarian use, you can’t beat a mono-stainless steel. Some stainless steel knives receive a bad rep, mainly I think because they are used on on mass produced knives where they either aren’t heat treated properly, or they use the wrong stainless knife steel to save on cost or the way the knife is ground (the geometry) was bad. In my opinion, the best knife steels out there today are stainless steels. The steel I use for my Stainless Range is AEB-L, a steel widely use by knife makers for its high hardness, exceptional toughness, great edge retention, and good corrosion resistance.

Geometry

The last aspect of design I am going to talk about here (but certainly not the least) is blade Geometry. This refers to how the blade is ground, which will directly relate to how it performs for different tasks, as well as affecting the strength of the blade and the weight. For the sake of brevity I wont talk about all the various types of grinds and angles and such, but if you want a deeper look I would again recommend Dr. Larrin Thomas’s book - Knife Engineering.

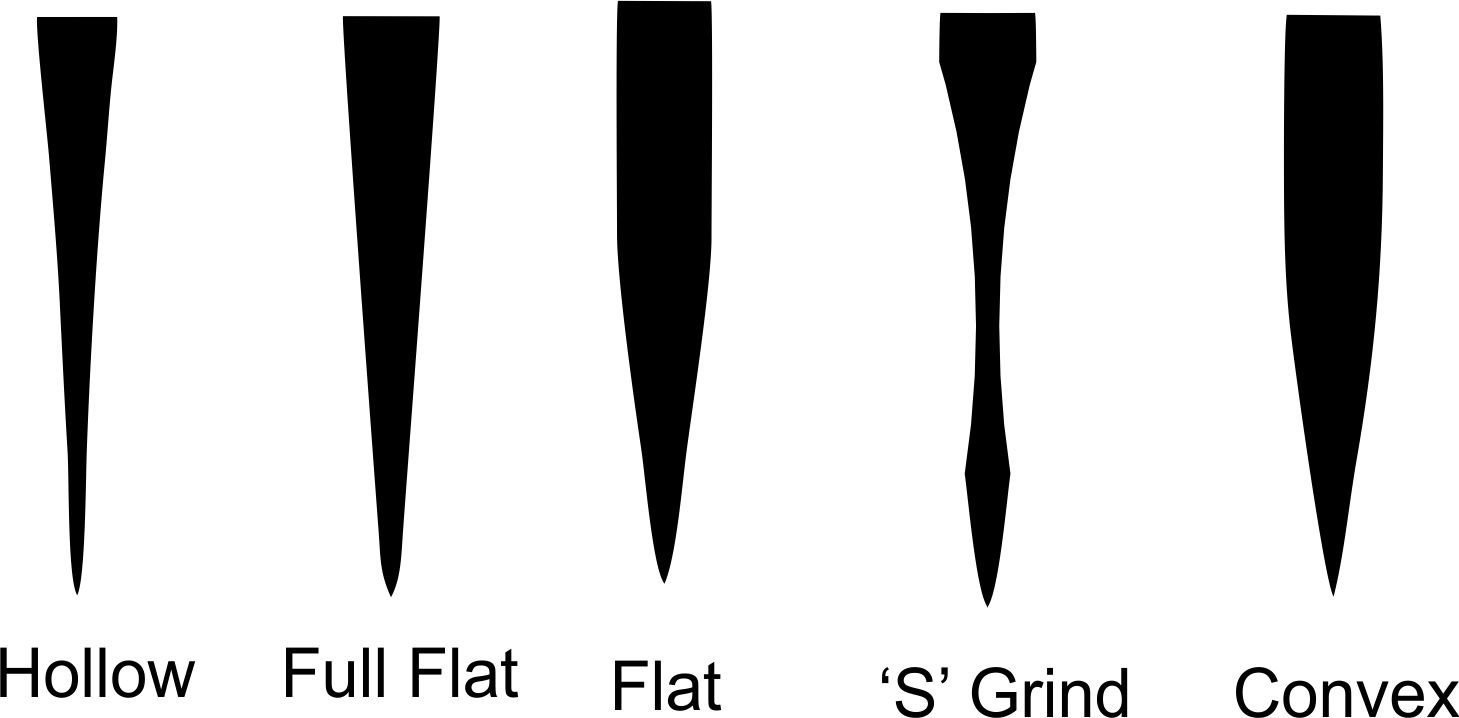

Full Flat grind

I am a fan of a full flat grind. The full flat grind is thickest at the spine for strength, but tapers down into a relatively thin edge for excellent slicing. More steel is removed from the sides, allowing for easier slicing and allowing the blade to move through mediums easier. A full flat grind will (typically) be stronger than a hollow grind, and cut better than the Flat grind. I also do a ‘double flat grind’ where I start with a normal flat grind that is a bit thicker than usual, but make the secondary bevel come higher up the blade, allowing for a thinner edge.

One of the downsides to a full flat grind is that because all of the blade is in contact with the food you are cutting, the food will stick to the blade forming a vacuum. This for me has always been a very minor issue, and during my 13 years so far of working in professional kitchens it hasn’t really bothered me or other chefs whom I have worked with. The double full flat grind that I do also helps to relieve this problem as it will break a vacuum in the angle change.

A FEW DEFINITIONS

Concave – shapes that curve inward. Think of how a crater curves in, or think "con-cavity".

Convex – shapes that curve outward, like a rugby ball.

Spine – the back of a blade, opposite of the edge.

Primary Bevel / Grind – Where the knife first begins to narrow into a cutting edge from the thickness of the main stock of the blade.

Secondary Bevel – the Edge of the blade.

Distal Taper - A knife blade should be thickest at the spine near the handle and taper to the thinnest point at the tip for better weight distribution and strength.

Often Found on Japanese blades or blades with a brut de forge finish, a Flat grind is a grind that comes flat from the edge but not all the way to the spine like Full Flat Grind. This might also be known as a saber grind. This is a very robust grind that can achieve good cutting potential while also remaining very strong, though you wont be able to grind it as thin at the edge as a Full Flat grind while keeping the spine at the same thickness.

Convex Grind

Flat Grind

The Convex grind is similar to a flat grind, however, instead of the bevel traveling flat to the edge, it in ground on a convex arc. This has a few benefits; it means the edge is well supported and robust, while at the same time having good ‘food release’ as the food will struggle to form a vacuum against the blade. This grind tends to be used on larger knives, cleavers, large chef knives and the like.

Hollow Grind

To make a hollow grind, the blade blank is applied to the surface of a grinding wheel or a belt passing around a wheel, taking a concave scoop out of the blade. The depth of the hollow will depend on the circumference of the wheel. Hollow grind don’t tend to be used on culinary knives as it will leave the edge too thin and therefore prone to chipping or bending. They also aren’t great for slicing vegetables as the blade will act more like a wedge that splits a vegetable rather than cutting it. This type of grind tends to be better suited for hunting or skinning knives.

‘S’ Grind

An ‘S’ grind combines either a full flat grind, a flat grind or a convex grind with a hollow grind in the middle of the blade. The idea of this is to improve the knives ‘food release’ by creating a hollow so that the food wont stick to the blade.

The jury is still out amongst the knife making community about this grind. I personally like it on a blade like a Nakiri or a small santoku however I dislike this grind on a chefs knife or Gyuto where I find that it makes the blade too light with a lack of a nice heft. Cutting through a big butternut squash or celeriac is easier with some weight behind the cut.